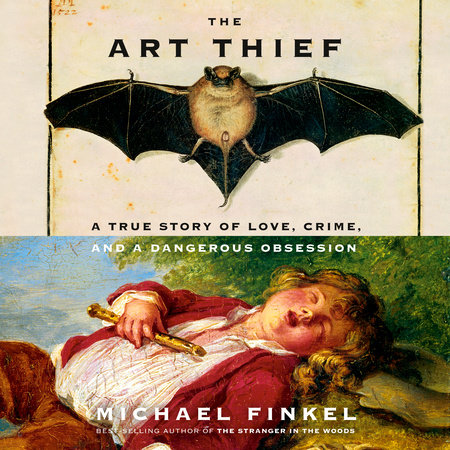

The Art Thief

By Michael Finkel

By Michael Finkel

By Michael Finkel

By Michael Finkel

By Michael Finkel

By Michael Finkel

By Michael Finkel

By Michael Finkel

By Michael Finkel

Read by Edoardo Ballerini and Michael Finkel

By Michael Finkel

Read by Edoardo Ballerini and Michael Finkel

Category: Biography & Memoir | True Crime | Art

Category: Biography & Memoir | True Crime | Art

Category: Biography & Memoir | True Crime | Art

Category: Biography & Memoir | True Crime | Art

Category: Biography & Memoir | True Crime | Art | Audiobooks

-

$18.00

Jun 25, 2024 | ISBN 9781984898456

-

$30.00

Jun 27, 2023 | ISBN 9780593744178

-

$28.00

Jun 27, 2023 | ISBN 9780525657323

-

Jun 27, 2023 | ISBN 9780525657330

-

Jun 27, 2023 | ISBN 9780593741696

340 Minutes

Buy the Audiobook Download:

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Cursed Bread

The Devil’s Playground

The Vaster Wilds

The Burning of the World

North Woods

Flirting with Danger

After You’d Gone

The World

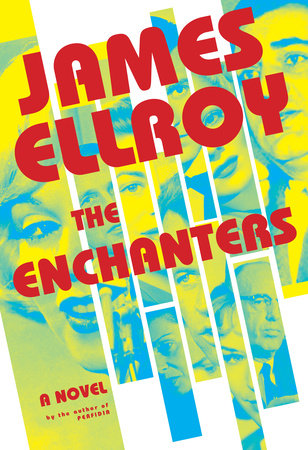

The Enchanters

Praise

A BEST BOOK OF THE YEAR: The Washington Post, The New Yorker, Lit Hub

“The Art Thief, like its title character, has confidence, élan, and a great sense of timing. It is propelled by suspense and surprises….This ultra-lucrative, odds-defying crime streak is wonderfully narrated by Finkel, in a tale whose trajectory is less rise and fall than crazy and crazier….Part of what makes Finkel’s book so much fun is that, without exception, [Breitwieser’s] strategies are insane.”

—Kathryn Schulz, The New Yorker

“A mesmerizing true-crime psychological thriller….The Art Thief develops the tension of a French policier, where the crook (for whom you alternately feel sympathy and disgust) has Maigret or Poirot hot on his trail. The final outcome is a shock. Mr. Finkel tells an enthralling story. From start to finish, this book is hard to put down.”

—Moira Hodgson, The Wall Street Journal

“Enthralling…In animated and colorful prose, Finkel summons the emotional intensity of a murder mystery. But old masters, not bodies, are missing….The Art Thief is about heists, yes, but it also speaks to much more.”

—Brandon Tensley, The Washington Post

“Exhilarating…Finkel’s narrative thrills and electrifies, until it all barrels toward inevitable capture, two shocking betrayals, and an astonishing conclusion.”

—Adrienne Westenfeld, Esquire

“Thrilling…Finkel deftly unspools the story of Breitwieser’s improbable years-long adventure.”

—Geoffrey Gagnon, GQ

“Meticulously detailed, [a] page-turning account….As much a crime caper as a psychological thriller, Finkel’s narrative interweaves gripping descriptions of Breitweiser’s in-plain-sight thefts armed with nothing more than stealth and a Swiss Army knife, a concise history of global art theft, and psychologists’ musings on Breitwieser’s unconscious motivations….Finkel deftly keeps us swaying between great sympathy for his central character and profound suspicion.”

—Jenny McPhee, Air Mail

“It is romantic to liken art thieves to Pierce Brosnan’s glamorous character in The Thomas Crown Affair. The reality is far less charming. Case in point: Stéphane Breitwieser, one of the most successful art thieves of all time. From roughly 1994 to 2001, Breitwieser executed more than 200 heists. The book’s first lesson? Europe has a lot of understaffed historic buildings. The second? Even a kleptomaniac with delusions of grandeur can be made mildly sympathetic in the hands of a skilled writer.”

—James Tarmy, Bloomberg

“The Art Thief benefits from a built-in ticking clock as time runs out for Breitwieser and his girlfriend. Finkel controls the pace effortlessly, broadening and narrowing focus from the day-to-day of the thieves to the intricate plotting of their thefts and a history of art crime, as well as who steals and why. That combined with mounting dread for the artworks’ fate makes for a heart-pounding read.”

—Maren Longbella, Star Tribune

“Finkel turns his extensive research and interviews into a suspenseful story that reads like a novel. He relates Breitwieser’s technique in vivid detail, and then shows us what happened to an estimated $2 billion worth of paintings, sculptures and other works. Finkel explores the relationships between Breitwieser and the women in his life, along with interesting bits of art history. A true-crime thriller that’s a work of art.”

—Suzanne Perez, KMUW Wichita

“Finkel has crafted The Art Thief with finesse and élan. He tells his tale of obsessive desires and ornate objects in measured and unadorned prose; employs a supple structure that separates the multiple threads of the tale while also exploring their weave; and advances the linear plot with narrative strategies that not only anticipate its foregone conclusion without giving it away, but also incorporate into the unfolding events his retrospective analyses of them….[Finkel] manages point of view with deftness and purpose….The Art Thief…morphs from an entertaining caper story into a claustrophobic study in pathology…An absorbing but disquieting read.”

—Charles Caramello, Washington Independent Review of Books

“This is an absorbing and astonishing portrait of a fascinating and complicated character—a riveting story of obsession and misplaced brilliance.”

—Kirk Wallace Johnson, best-selling author of The Feather Thief and The Fishermen and the Dragon

“In this masterful true crime account, Finkel traces the fascinating exploits of Stéphane Breitwieser, a French art thief who stole more than 200 artworks…turning his mother’s attic into a glittering trove of oil paintings, silver vessels, and antique weaponry….Drawing on art theory and Breitwieser’s psychology reports, Finkel speculates on his subject’s addiction to beauty….It’s a riveting ride.”

—Publishers Weekly, starred review

“The tale of a strong candidate for the title of ‘most prolific art thief ever….’ Finkel’s play-by-play of each theft has the pacing and atmosphere of a good suspense tale….The author describes each acquisition as well as Breitwieser’s simple but effective methods….Finkel’s extensive research, survey of art history, and hours of interviews with his subject combine for a compelling read.”

—Kirkus

“A riveting ride….An engrossing true crime narrative….Obsessive crime, dangerous beauty, ill-fated love: The Art Thief is the stuff of noir fiction, made all the more compelling and audacious for its authenticity.”

—BookPage

“From the opening chapter, Finkel’s tight prose heightens the drama of each theft, as Breitweiser and his girlfriend Anne-Catherine Kleinklaus, who serves as his lookout, enter Belgium’s Rubens House amid visitors and guards….A fascinating read. Finkel will have art history and true crime lovers obsessively turning the pages of this suspenseful, smartly written work until its shocking conclusion.”

—Library Journal

“The Art Thief is both comprehensive and completely absorbing. It will have you wondering, as judges and juries did, if the defendant is a career criminal or simply an aesthete.”

—Lorraine W. Shanley, BookReporter

21 Books You’ve Been Meaning to Read

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In